My Information Operating System Part 3: Connecting

Disclosure: This article uses affiliate links. Items I recommend may generate a small commission for me if you purchase them via my link.

[!NOTE]

This is Part 2 of a 3-part series. You can find Part 1 here, and Part 3 here.

Now that you’ve read about how to read effectively and collect your notes and highlights, it’s time to get to the fun part: synthesizing something new (articles, blog posts, project ideas, research topics, etc.) from that information. After all, what’s the use of knowledge if you can’t do anything with it?

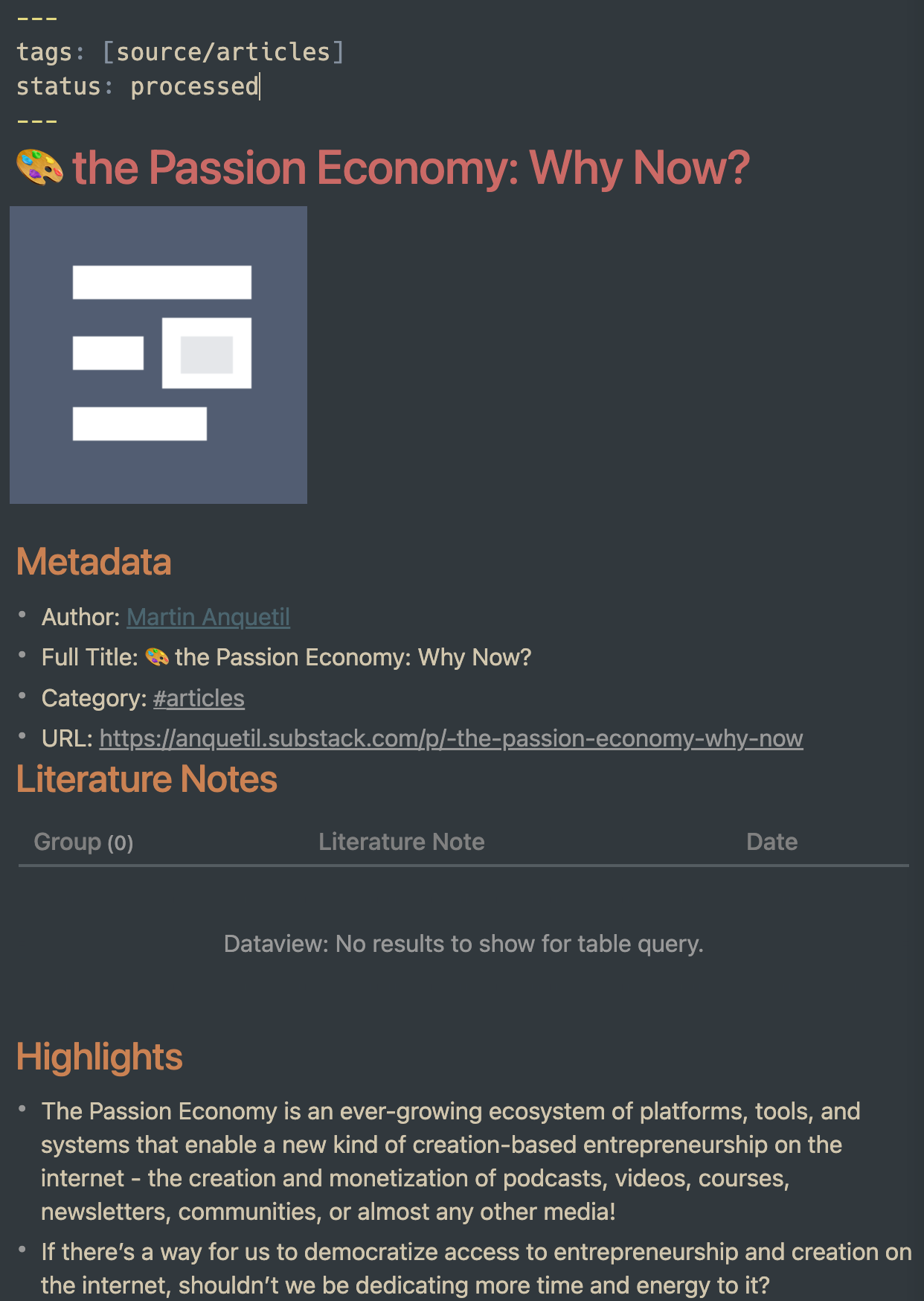

This process all happens in your graph personal knowledge management (PKM) tool of choice, such as Obsidian or Roam. I even wrote this whole series in Roam! First, take a look at a fully processed article:

This image is a partial view of my notes on this article in Obsidian, but it should give you a good idea of the overall structure and process.

When an article first comes in from Readwise, it has this structure but only the highlights filled in. These highlights then undergo a form of progressive summarization.

First, you pick out particularly important, inspiring, or noteworthy passages and highlight them in Roam. If you have notes that you took while reading, those get moved to the Literature Notes section with a block reference to the associated highlight (in Obsidian, literature notes are separate notes that get pulled into the source note via a Dataview query. You should make sure to pick out any concepts that deserve a page and make them into one with double brackets as I did with Passion Economy and Entrepreneurship above.

The rest of the progressive summarization steps typically happen when/if you revisit the piece, but you can do them all at once if you prefer as well. These steps include bolding highlighted passages that are still very relevant, then building up a summary of the piece on each revisit. This process allows you to quickly judge the relevance of an article as you visit and use it.

While I’ve found progressive summarization to be useful, some have argued (convincingly) that summarization alone is one-dimensional. I tend to agree. You can’t always judge what information you will find relevant in the future, and it doesn’t hold much space for commentary or understanding more general concepts.

That is why the rest of the sections exist. As you highlight, bold, and move your reading notes into the Literature Notes section, you may get ideas, inspirations, and insights. These will filter into the higher up sections:

- Ideas

- Literature Notes

- Transient Notes

Ideas are somewhat self-explanatory, although they may be better worded as “Inspirations.” This is where new thoughts that were inspired by the reading go. These ideas should reference the passage that inspired them and receive the tag #Waiting. Doing this will add the idea to my Writing Inbox that queries for Ideas with the Waiting tag to remind me to refine them further. When I process my inbox, I will refine them into research topics, article ideas, or projects as appropriate and changed the #Waiting tag to #Processed.

[!NOTE] This process is a bit different in Obsidian. The Ideas header - as you see in the image above - isn’t present here. You can modify the Readwise template provided in Part 2 to include the header, but I’ve been making new Idea notes right when the inspiration strikes and referencing the source note from there. Since tags are used differently in Obsidian, the status of the idea is tracked via the YAML frontmatter of an Idea note.

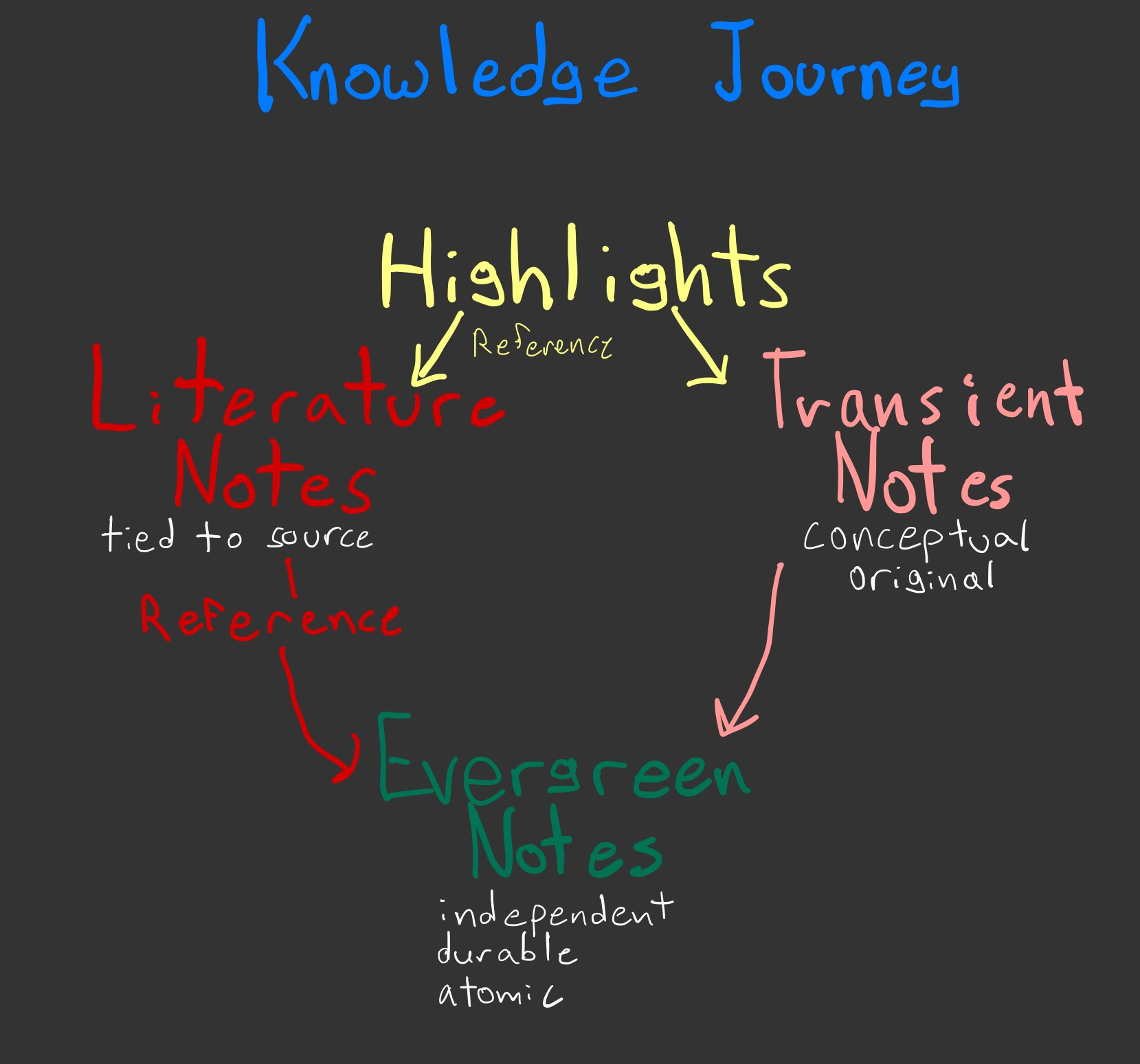

Literature Notes are generally where your reading notes will live, as well as any other commentary you have on the reading. These notes and ideas are tightly coupled to the reading material. These should have block references to any highlights that they draw from, be heavily backlinked, and can serve as reference points for any transient notes and, potentially, evergreen notes (which you’ll learn about soon).

Another way to look at literature notes is as signposts for how you were thinking when you read a particular passage. If you were reading a book, these notes would be the marginalia.

Transient Notes are more conceptual. I like to think of them as transcendent as they’re not tightly coupled to a single source. You can also think about them as approaching the Platonic ideal of the concept. They can be conclusions you draw, the concepts you learn about, and more. The main requirement is that you could find other pieces that support, deny, or reference the higher concept you’re writing about.

Your literature notes and highlights serve as the supports for your transient notes. Just like your literature notes have block references to the supporting highlights under them, your transient notes will have block references to the supporting literature notes or highlights under them.

Like ideas, transient notes get a #Waiting tag, which allows them to get picked up in my writing inbox. As the transient note waits there, I may pick up similar transient notes or add more references from other pieces to that transient note. That’s a signal that it could become an evergreen note.

[!NOTE] As noted above, the inline tag workflow is most suited to Roam. In Obsidian, my preferred workflow with transient notes is to use Obsidian’s built-in unique note creator plugin to create them and then process them at a later time.

Wait, this wasn’t on the list!

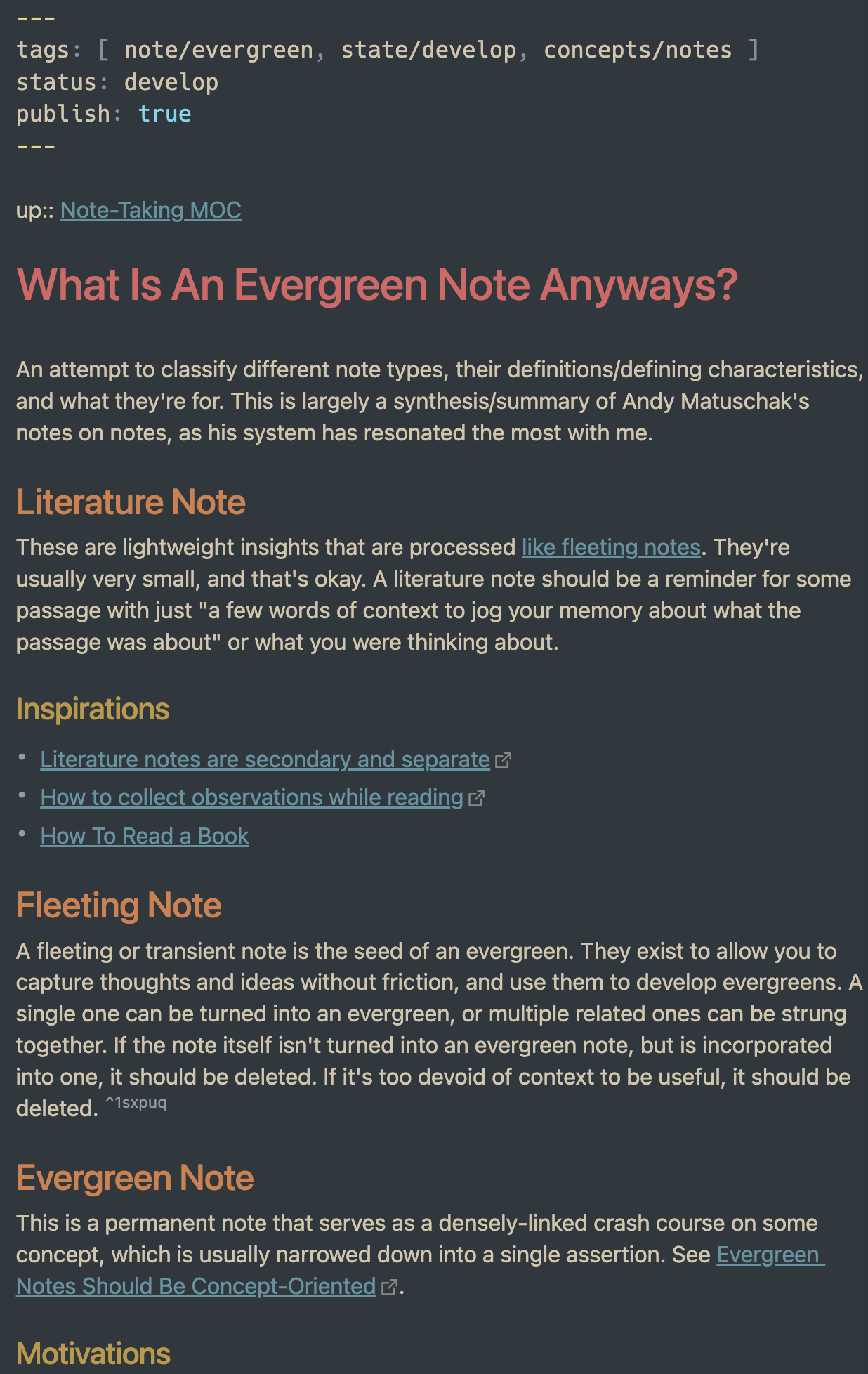

Evergreen notes don’t appear in the template because they’re independent, durable, and atomic. They are independent of any source articles, they are long-lasting and can evolve with new information (durable), and they capture a single concept in its entirety (atomic).

The basic structure of an evergreen note can take many forms, but I’ve found that having one in mind can help guide your work. This is the structure I used in Roam:

- Title: This is like an API to the knowledge, and it’s essential to design these well because they are vital to discovering the proper notes when you need them.

- Body: This is the note itself. The body usually has 3 to 4 sentences, is heavily backlinked, and describes the concept concisely.

- Tags: These are related topics that don’t appear directly in the body. In Roam, especially, these serve to enhance the discoverability of your notes.

- References: Here, you’ll place the literature notes, transient notes, and occasionally highlights that went into building the note. These should all take the form of block references to establish the linkage in your graph. The references, once processed, should lose the #Waiting tag and gain the #Processed tag.

In Obsidian, the template is a little different, but only in that tags and the note’s status (develop/tidy/boat, adapted from Nick Milo’s Linking Your Thinking) live in the YAML frontmatter of the note.

Here is an example of one of my evergreen notes:

In this note, you can see that the title has some keywords to aid in searching, the body of the note has both internal backlinks and external links, the tags are well-populated, and several references drive the concept’s formulation.

[!NOTE] To explore this note and its relatives more thoroughly, check it out in my published notes.

How did I write this? Andy Matuschak devised a processing loop for processing notes into evergreens:

- Write a broad note to capture the main idea of a group of related transient notes.

- As you go through the clustered transient notes, try to find and write more fine-grained notes for more nuanced atomic ideas.

- Search for any relevant notes that relate to the new ones. You can link them, merge them, or revise as necessary.

- Improve the broad note from step 1 with everything you learned from writing the notes in step 2 while keeping it focused. Prune and update other notes as needed.

- Repeat.

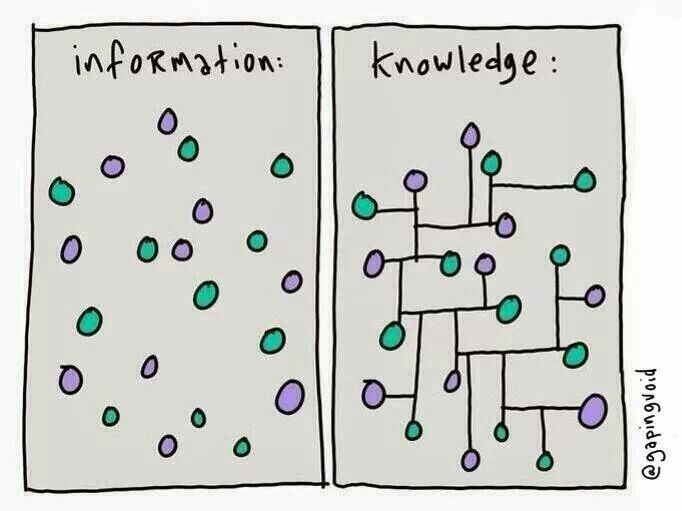

With a well-done evergreen note, you’ll have transformed information into knowledge by making deep connections to related topics, other evergreen notes, and sources. You can then uncover insights and synthesize new knowledge by remixing your evergreens and producing new work from them, such as an article, a book, or a research project.

It’s imperative to know that you shouldn’t do this for everything you read. Think of your notes as a garden: you attend to, ignore, grow, and prune different plants and sections according to your needs at the time. Not everything is important enough to be fully summarized, and not everything is inspiring enough to contribute to your broader conceptual knowledge.

To summarize, when you bring a source into your favored PKM tool, you will have highlights, and then do some or all of the following:

- Progressive summarization of the highlights.

- Write ideas, tightly coupled literature notes, and loosely coupled transient notes.

- Use ideas to inspire projects, research topics, or articles.

- Use your highlights, literature notes, and transient notes to form evergreen notes.

- Use your evergreen notes to uncover insights and synthesize new knowledge outputs.

This is the knowledge journey:

Summary⌗

This wraps up the (very long) series on my information operating system. After all this, I think a quick recap is in order.

In Part 1, you learned about reading effectively by:

- Understanding the four levels of reading, from How to Read a Book.

- Having a conversation with the author by highlighting and taking notes as you read.

- Using tools to organize and annotate your library like Matter, Instapaper, Calibre, and Kindle.

In Part 2, you learned about collecting your notes and highlights by:

- Using Readwise to collect your notes and highlights from all your sources.

- Revisiting and reviewing your notes and highlights with Readwise’s Daily Readwise feature.

- Preparing and exporting your notes and highlights from Readwise to Obsidian or Roam.

And then here in Part 3, you learned how to synthesize new knowledge by:

- Using progressive summarization on your highlights.

- Writing inspired ideas, literature notes, and transient notes.

- Using inspired ideas to form projects, research topics, and writing topics.

- Transforming information into knowledge by creating evergreen notes from transient and literature notes.

- Synthesizing something new from a collection of evergreen notes.

I hope this gives you a broad overview and some inspiration to taste, chew, digest, and transform information into knowledge with Roam. Do you have a system for processing information into knowledge? Has Roam changed how you interact with information?